Causes and Correlates of Charitable Giving in Estate Planning:

A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Examination of Older Adults

Final Report

Submitted to the AFP/Donor Compass™ Planned Giving Research Grant Program

July 2008

Russell N. James III, J.D., Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

University of Georgia

For more information, visit www.legacyleaders.com or call 215-351-5180.

Who is likely to add (or remove) a planned charitable estate gift? When are they likely to do it? Until now, these questions could only be answered based on personal experiences or a handful of examples. New research, funded by a grant from the Association of Fundraising Professionals through the support of Donor Compass™, Inc. has now shed some light on these basic questions. Previous research on the topic had used only post-mortem records or one-time surveys, but none had tracked individuals over a period of years. Russell James III, J.D., Ph.D., of the University of Georgia’s Institute for Nonprofit Organizations, authored the new report. “This study was the first nationally-representative, longitudinal analysis of charitable bequest behavior among older adults,” explained Dr. James. The study was longitudinal, meaning that it followed the same group of individuals over several years. It tracked over 20,000 older Americans (over the age of 50) between 1995 and 2006 as part of a larger Health and Retirement Study. The research attempted to answer three basic questions. Dr. James explained, “We wanted to know who had charitable estate plans, who added charitable estate plans, and who dropped charitable estate plans.” Each of the three questions can have different relevance for planned giving professionals. For example, if you were working with a group of donors who had already named your organization in a will, you might be more interested in factors that increased the likelihood of removing a charitable estate component. But, if you were targeting prospective estate donors, you might want to know who had charitable estate plans or who was likely to adopt a charitable estate plan in the near future.

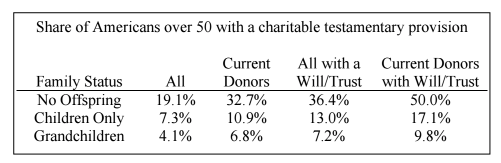

The new study, soon to be published in the academic journal nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, produced important findings in three areas. The first finding was that charitable estate planning was not common. Among those over age 50 who were donating more than $500 per year to charitable organizations, fewer than 9.5% had a charitable estate plan. Theoretically, some of these donors might add an estate gift before death. However, both age-mortality adjusted projections and the estate distributions from recently deceased study participants suggested that, ultimately, only 10% to 12% of donors will die with any charitable estate provision. Dr. James said, “For those who think the generational transfer will automatically flood their organizations with resources, it’s time to think again. Without putting in the hard work of generating these planned gifts, 90% of donor mortality will simply result in lost current giving.” The second major finding was that the most dominant factor in predicting charitable estate planning was not wealth, income, education, or even current giving or volunteering. By far, the dominant predictor of charitable estate planning was the absence of children. Among current donors over age 50 who had already completed a will or trust, only 9.8% of those with grandchildren included a charitable component. For similar donors without any offspring, 50% had a charitable estate plan. This five-to-one ratio of charitable estate planning among childless individuals as compared to grandparents was also true among all seniors, all seniors with a will or trust, and all seniors who were current donors.

While some connection between offspring and charitable estate giving was expected, the magnitude of the effect was surprising. Consider this comparison. Senior adult “A” makes substantial charitable gifts, volunteers regularly, and has grandchildren. Senior adult “B” doesn’t give to charity, doesn’t volunteer, and has no children. “A” and “B” are otherwise demographically and financially identical. Who is more likely to have a charitable estate plan? Answer: person “B” – by a wide margin. In fact, even if “A” had more income, or education, or assets, he is still less likely to leave a charitable estate gift than “B”. The table shows the effects of a variety of factors in predicting the likelihood that a senior adult will have a charitable estate plan. Considering two otherwise demographically and financially identical senior adults, how does the likelihood of one of them having a charitable estate plan change if he or she:

1. Has a graduate degree (v. high school) +4.2 percentage points

2. Gives at least $500 per year to charity +3.1 percentage points

3. Volunteers regularly +2.0 percentage points

4. Has a college degree (v. high school) +1.7 percentage points

5. Has been diagnosed with a stroke +1.7 percentage points

6. Is ten years older +1.2 percentage points

7. Has been diagnosed with cancer +0.8 percentage points

8. Is married (v. unmarried) +0.7 percentage points

9. Has been diagnosed with a heart condition +0.4 percentage points

10. Attends church at least once per month +0.2 percentage points

11. Has $1,000,000 more in assets +0.1 percentage points

12. Has $100,000 per year more income not significant

13. Is male (v. female) not significant

14. Has only children (v. no offspring) -2.8 percentage points

15. Has grandchildren (v. no offspring) -10.5 percentage points

This strength of the relationship with childlessness may suggest a modification to standard strategies of targeting potential estate donors. Often fundraisers target their largest current donors first and work their way down according to annual giving level. While this strategy is still valid, it may be most effective if combined with a simultaneous strategy of identifying supporters without children. Finally, the study examined those who either added or dropped a charitable estate provision during the tracking period. Altogether, 1,306 individuals reported dropping the charitable component of their estate plan during the course of the study. Conversely, 1,477 seniors reported adding a charitable component during the study. What factors accompanied these changes? Dropping a charitable estate plan was most strongly associated with becoming a grandparent. Similarly, becoming a parent for the first time significantly increased the likelihood of dropping a charitable estate plan. Another hint that the charitable estate plan would be dropped was cessation of current giving. Finally, a substantial drop in self-reported health also increased the likelihood that the charitable component of an estate plan would be dropped. Predicting a charitable estate planning change

The changes most likely to predict the removal of a charitable estate plan:

1. Becoming a grandparent

2. Becoming a parent

3. Stopping charitable giving

4. A drop in self-reported health

The changes most likely to predict the addition of a charitable estate plan:

1. Starting to make charitable gifts

2. An improvement in self-reported health

3. An increase in assets

On the other hand, an increase in self-reported health increased the likelihood of adding a charitable estate component. In addition, a substantial increase in wealth raised the likelihood of adding a charitable estate component, as did beginning to make charitable gifts. Finally, the biggest factor that reduced the likelihood of adding a charitable estate plan was becoming a grandparent. Oftentimes research studies confirm common sense impressions. Even so, such studies can separate common sense truth from common sense myth. These new findings on charitable estate planning provide a solid research-based foundation for fundraisers to develop their own day-to-day best practices for acquiring and retaining charitable estate donors.